How Cox's mistakes statutorily disqualified him from the ballot

News Analysis

Spencer Cox's claim to be the Utah Republican gubernatorial nominee is flawed by not one, but two, critical statutory requirements. One apparent failure is currently in dispute because of an unusual and controversial decision with the Utah State Supreme Court in which it prescribed internal Utah GOP party mechanisms based on ambiguous language. The other statutory failure, however, is without ambiguity: he failed to reach the threshold of petition signatures required to be on the general ballot, as shown by a Utah legislative audit. And this failure was caused by his own strategic mistakes, in contrast to other candidates who met the threshold with more intelligently-assessed gathering and timing.

1. Cox failed to be competitive at the Utah GOP convention

The first, but perhaps ambiguous, flaw is based on the statute that allows Utah qualified political parties to determine a nominee through either a convention or a primary election. Utah GOP rules state that a candidate that wins 60% or more delegate votes at its convention is automatically its nominee. Cox himself can be found on historical videos and on multiple other sources emphasizing this rule, assenting to it, and defending it.

But in 2016, Cox, as Lt. Governor, took an argument to the state high court that the Utah GOP must have a primary election in all cases, perhaps anticipating that he could not win the base support of the GOP delegates in a future gubernatorial run because of his increasing open borders rhetoric and sympathetic statements for the tenants of the Democratic party platform. The Utah high court, in a puzzling, interventionist, and controversial decision, sided with Cox so that it required a primary for the Utah GOP. That decision is currently under an appeal request to the United States Supreme Court.

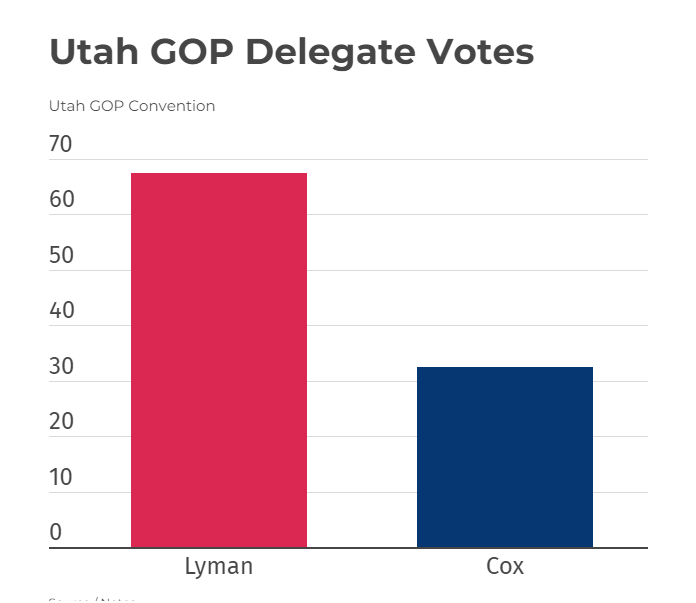

In 2024, Spencer Cox lost the convention delegate vote in a landslide to Phil Lyman, making Phil Lyman the apparent Utah GOP nominee.

2. Cox miscalculated validity rates and timing for his signatures

Cox pursued the route to the ballot that he previously argued for with a signature petition. But unlike the ambiguity and dispute surrounding the convention requirement, the petition signature requirement is clearly detailed by statute in specifying both the threshold and the methods to determine its fulfillment: 28,000 statistically likely valid signatures (Utah Code 20A-9-408). A subsequent Utah legislative statistical audit clearly shows that Cox numerically failed in qualifying for the ballot because he did not meet the threshold of valid signatures needed.

In their oral presentation, the legislative audit group elided over the valid signature numbers–-and proffered statutorily-irrelevant opinions on Cox's efforts and timing. But their actual analysis of the number of signatures and the statistical likelihood of qualification (allowed by statute to be accepted) showed that Cox did not submit enough extra signatures to compensate for the invalid signatures he collected.

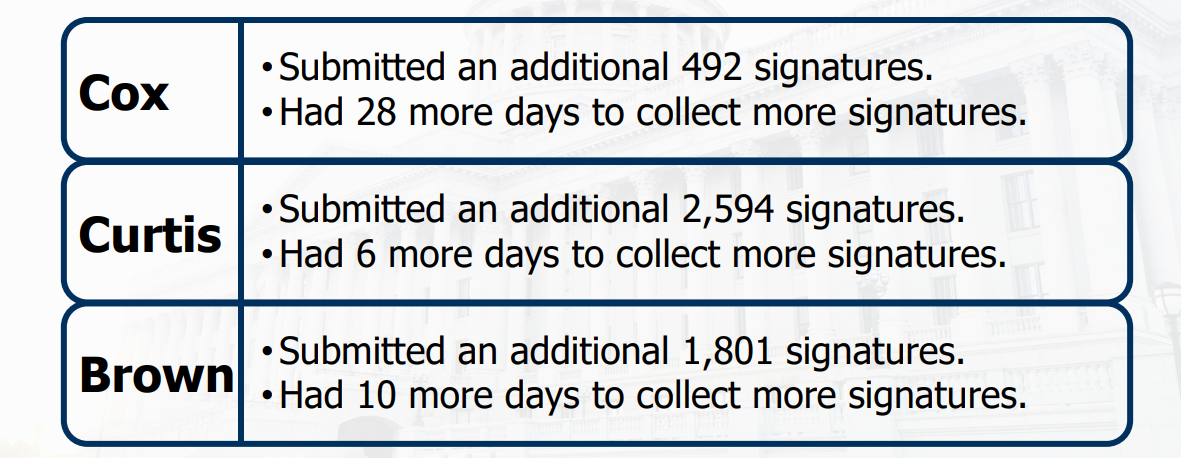

This is in contrast to the samples they collected from two candidates in other elections. While John Curtis and Derek Brown each submitted thousands of extra signatures to account for typical signature rejection rates, Cox had many fewer signatures left uncounted: 492.

Further, Cox submitted the signatures prematurely, perhaps in an effort to show how quickly he could present support for his candidacy after losing the Utah GOP convention election by such a wide margin. Whatever the reason, Cox submitted the signatures before collecting a more statistically safe amount of extra signatures, despite knowing that he could not add signatures to his petition after submission.

Other Utah media have misrepresented the statutory requirements to qualify for the ballot. They have argued for considerations such as level of effort ("he did everything he could do") or his miscalculated timing ("he could have had more time to collect signatures"), none of which are expressed in Utah statute as factors, much less as exceptions to nullify clear, existing statute. Despite the assertions of other Utah media, and those in state offices who are subject to the good graces of an incumbent governor, Cox's own tactical mistakes unequivocally disqualified him from legally being on the 2024 ballot as the nominee for the Utah Republican party.